XX: Within Our Gates (USA, 1920; dir. Oscar Micheaux; scr. Oscar Micheaux)

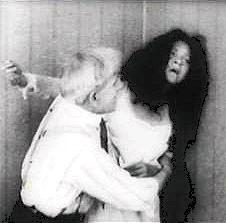

(USA, 1920; dir. Oscar Micheaux; scr. Oscar Micheaux)IMDb The most famously racist movie in American cinema is D.W. Griffith's 1915 epic The Birth of a Nation, a film whose boundary-pushing visual grammar and sophisticated devices for managing parallel narratives are deservedly celebrated, and yet whose white-supremacist mythomania is so overt and passionate that actually watching the film is invariably worse than anything you might hear about it in advance. Until you have beheld the Ku Klux Klan riding valiantly to the rescue of an imperiled white lily of Southern womanhood, you have not experienced the full, gobsmacking force of the racist musculature behind early American visual culture. (Wasn't it kind of me to say "early"?) Enraged by what he saw in The Birth of a Nation, African-American filmmaker Oscar Micheaux rode to his own rescue and filmed Within Our Gates—one of his two most famous films (the other is 1925's Body and Soul), but nonetheless obscure to most moviegoers, even those who retrospectively recognize the fundamental disgraces in Griffith's movie. This circumstance actually speaks to another American problem, wherein we have better memories for Faustian masterpieces than for exemplary acts of redress. Indeed, Within Our Gates was deemed lost for many years before it resurfaced just over a decade ago, in mislabeled film canisters in a vault somewhere in Spain. Knowing the severe obstacles this film has faced for decades just trying to get itself seen—not to mention the obstacles you'll encounter trying to see it, unless you live near a university library, or unless TCM is having an especially emancipated day—only adds to its blunt force once unveiled. Rather than a white actor in blackface chasing a histrionic Mae Marsh, Within Our Gates sports a harrowing sequence in which Sylvia Landry, its African-American protagonist, is not only beaten and sexually aggressed by a white man, but by one who comes to realize amidst this very encounter that he is her father—speaking not just to his brutishness in the present moment but to an entire history of disavowed sexual violence and natal alienation. Just as thunderous, both in its anger and in its bold execution, is a long flashback sequence that details the lynching of Sylvia's family, a passage which was customarily excised by craven projectionist even when Gates played to American audiences in 1920. The desperate physicality of the actors in these sequences, as well as their comportment in the more serene but equally interesting passages of the movie, are a succinct rebuttal not just to American memories of its racial past but to the dominating aesthetic of American silent features, which usually opted for a gentility and a stylized theatricality that Micheaux frequently eschews. Lead actress Evelyn Preer, a bright light of the African-American stage, has a soft but womanly poise that offers key counterpoint to the willowy fragility with which Griffith tended to shoot Lillian Gish. Furthermore, Micheaux, who worked without a credited cinematographer, is a cunning visualist, alternating abstract and realist backgrounds behind characters in seemingly straightforward dialogue scenes, so as to comment subtly on the varying moral depth of their points of view, their relation to or else their avoidance of the world they mutually inhabit. Within Our Gates is full of surprises, following a multitude of characters and plotlines without settling into predictable allegiances. Micheaux's critiques of bad habits within the African-American community are as lucid as his indictments of white-supremacist ideology. The film wholly avoids a Manichean division between black saints and white predators, and the introductions of romance and religion among the film's active concerns do interesting things to our views of several characters. The closing scenes are unforeseeably optimistic, and Gates has taken its licks over the years for making this turn, though it seems to me that the thinly motivated dissolve amidst the final shot squares it quite self-consciously in the realm of fairy tale. Of course, the most delicious surprise in Within Our Gates is that it exists at all, against the odds of America's post-WWI self-deification and despite Micheaux's omission from too many debates and film texts where he rightfully belongs. One particularly succulent reward came in 1992, the fourth year in the cycle of National Film Registry inductees, when Within Our Gates entered the Library of Congress' most esteemed collection of American films right alongside The Birth of a Nation. In the national archives at least, but hopefully in other places too, Micheaux can call Griffith's bluff in perpetuity. There is more than one way to write history in lightning. |

| Permalink | Favorites | Home | Blog |